Commentary | Ed Pulford and Trần Mai Hương, Socialist State Subjectivity: The Changing Stakes of Vietnam’s Ethnic Classification Policy

On August 16, 2024, the online newspaper of the Communist Party of Vietnam, Báo điện tử - Đảng Cộng sản Việt Nam, published a story covering the ongoing rollout of a new generation of biometric national identity cards.[1] Reporting from Sông Công, a mid-sized town in the northeast of the country, journalist Lê Hà’s article focused mainly on the issuance of the cards to children, a project which – according to the headline – was nearing the “finish line” in Thái Nguyên province. Yet even amid the report’s positive tone, standard for such official publications, there were hints that the process was not as linear as the running race imagery would suggest. As noted by a police lieutenant colonel in an outlying area of Sông Công, some local people had been slow to respond to the initiative. In particular, he said, fewer children of local minority groups including Sán Dìu, Tày, Nùng, Dao and Mường, had received the new cards, something he attributed to the fact that their parents lived in remote areas, moved around a lot, lacked smartphones to access the government’s online service portal, and did not see why their children needed ID cards. According to this police officer, these factors had made it hard to communicate the benefits of the new documents and find opportunities to scan fingerprints and other information necessary for their production.

This assessment of the situation in one location in Thái Nguyên evokes several themes familiar to anthropologists of ethnopolitics in Vietnam. The association of minority ethnic groups (dân tộc thiểu số) with remote and “hard to reach” areas, unpredictable mobility, and technological underdevelopment are all established tropes. So too are recurrent state efforts to manage these communities who, classified by the state into fifty-three official groups, number around fifteen million people (fifteen percent of the national population).

Yet the lieutenant colonel’s description of minority citizens eluding incorporation into this latest iteration of the Vietnamese party-state’s documentary regime also hints at a subtle irony and a contemporary issue which merits further attention from anthropologists: just as state efforts to encompass minorities has attained a new biopolitical intensity, so too has the idea of minority identity shifted in important ways. Unlike on previous laminated cardboard ID cards, the dân tộc or “ethnicity” category no longer appears on the new plastic versions. This has important implications for how ethnicity is understood in Vietnam, and in multi-ethnic post-socialist states more generally. What is at stake is multi-scalar state subjectivity: what and who the state is understood to consist of, and the contours and categories through which individual citizen-subjects are situated in relation to the overall state project.

Reform and response

On November 22, 2023, the National Assembly of Vietnam approved an updated Identification Law (Luật căn cước) to take effect on July 1, 2024. Confirming that ethnic identity will not feature on the latest national ID, known as the CC (Căn cước),[2] the law further mandated that new biometric document will replace all paper cards (Chứng minh nhân dân), which ceased to be valid from December 31, 2024 (Image 1).

This was not the first change to the format of the card, as previous reforms included the 2012 extension of ID numbers from nine to twelve digits and the 2021 addition of an electronic chip.[3] In addition, ethnic and religious (tôn giáo) categories have been retreating from prominence for several years, first disappearing from their former place on the card’s reverse side when a card known as the CCCD (Căn cước công dân) appeared in 2016. But what is different on this occasion is that, while obtaining the CCCD was optional, all citizens are now required to get a biometric card. It is therefore only in the past year or so that many citizens have moved directly from a laminated paper card which displays dân tộc to a shiny plastic one which does not. The new card details the holder’s identification number, name, date of birth, sex, nationality (quốc tịch meaning citizenship, distinct from ethnicity), place of origin and place of residence. Ethnicity is still linked to the card, but can only be accessed by scanning a QR code which is linked to the National Population Database.[4] Only certain state officials have access to this database, and so ethnicity is for their eyes only.

The motivation for these changes has been difficult to discern,[5] but in the context of other recent policies, several possible explanations emerge. First, Vietnam’s government has of late exhibited a heightened interest in protecting data it deems “sensitive” (nhạy cảm) with an April 2023 decree (13/2023/NĐ-CP) defining types of information which should be treated as such.[6] Yet the new “sensitivity” around the idea of dân tộc is curious given that its appearance on earlier cards suggested that it once constituted a core feature of a citizen’s explicit identification with the socialist state. An important factor to consider, we suggest, are the different scales at which sensitivity operates. In official pronouncements, this has been connected to notions of individual privacy of the kind which circulate in global discussions of data and identity. Yet the Vietnamese state’s long history of population surveillance and censorship raises questions about its commitment to personal privacy in general. More credibly, and also operating at an individualized scale, has been a second official motivation, namely reducing discrimination. Government social programs aimed at minority groups, such as sustainable poverty reduction and rural development, all have “eradicating ethnic discrimination” (xoá bỏ phân biệt chủng tộc) as key goals.[7] Yet still ambiguities remain. A November 2023 article in newspaper Dân Trí noted that removal of the ethnicity category may in some cases reduce ethnicity-based discrimination, but in others it may have the opposite effect since it will be more difficult for minority citizens to prove their status in order to exercise rights or access social services.[8] Moreover, minority groups are often less connected to technological infrastructure, face language barriers, and have low levels of digital literacy, complicating the state’s image of seamless digital governance. By way of reassurance, Dân Trí noted that the relevant information remains “conveniently” (thuận tiện) accessible in the National Population Database via the QR code. Yet convenience is a subjective experience primarily enjoyed here by state actors, and this in turn may aid us in discerning whose “sensitivity” really matters here. What appears paramount is the state’s, rather than individuals’, sensitivity around ethnicity, rooted in longstanding political concerns over the fraught and often conflictual history between the country’s Kinh majority and ethnic minority groups. For much of modern Vietnam’s history, the latter have been viewed by the state as inhabiting sensitive borderlands (phiên giậu) vulnerable to “reactionary forces” (thế lực thù địch) domestic and foreign.

This leads us to a third, overlapping, explanation for the move, namely that it may represent the latest step in official efforts to build a "one Vietnam" image. In line with messages directly from the Communist Party leadership that no one be left behind (không bỏ ai lại phía sau) and everyone be identified as Vietnamese rather than by their ethnic minority title (tộc danh), emphasizing collective identity over ethnic distinction has been a key part of recent state initiatives.[9] Indeed, also targeted for biometric registration are persons living in Vietnam who either have Vietnamese origins but no citizenship, and members of the overseas Vietnamese (Việt kiều) community.

Whatever the government’s motivations, the measures have elicited a range of responses - not all of them positive - from members of Vietnam’s non-Kinh communities. This was reflected during our fieldwork in the summer and autumn of 2024, which included interviewing members of the Nùng ethnic group who had moved from northern hometowns to Hanoi. Thanh (a pseudonym), who was working as a tour guide after earning a degree in tourism, carried both his old CMND and his newer CCCD with him and was happy to take them out and allow us to compare. The disappearance of dân tộc was, he felt, not a particularly major issue: Vietnamese society was more mixed these days anyway, and people thought little about ethnic issues in their everyday lives. Such a view was notable given that some of Thanh’s assignments saw him leading tour groups both to minority areas in the north close to his own hometown in Lạng Sơn province, and to a park on the outskirts of Hanoi where Vietnam’s ethnic groups are the main theme. But these experiences only appeared to have reinforced Thanh’s sense that ethnicity was a matter of leisure, a view consistent with other interlocutors who considered their professional and academic lives in bustling Hanoi to be largely detached from “ethnic” issues.

Yet other interlocutors were considerably less comfortable with the change. Lien, a researcher in her forties, observed that the new policy essentially looked like a measure to make Vietnam more similar to Western multicultural societies, but it was clear that she felt that something was being lost in the process. Aside from her own pride in her Nùng identity and interest in preserving culture, cuisine and ritual in the capital, she was concerned over the difficulties minority people could face in proving their ethnic status in the future. Her children, whose father was Kinh, had benefited from a modest credit boost on their university entrance exams but she wondered if birth certificates would now be required to access such minority entitlements. Lien was not alone in articulating such feelings; in 2022, one query to an online legal advice portal recounted an interaction with a local official who requested evidence of their minority status. A sudden realization of a lack of documentary proof left this person feeling upset (phiền), wondering whether this information existed anywhere at all.[10]

The reforms have also tapped into longstanding grievances among some ethnic groups. Despite strict media censorship, local officials have drawn attention to opposition from Vietnam’s Khmer community precisely by condemning it. The public security section of the government website for Vĩnh Long Province (where the majority of Khmer people live) has issued warnings that “reactionary forces” may be seeking to take advantage of identity card changes to incite Khmer people to disrupt national unity. According to local authorities:

Now on platforms like Facebook, the VOKK [Voice of Khmer Kampuchea Krom] website, Prey Nokor News, and other channels associated with the organization World Khmer Kampuchea Krom Federation - KKF, numerous posts and images of the new CCCD frame it as a deliberate attempt by the government to erase the ethnic and religious identity of the Khmer people, accusing authorities of pursuing an assimilation agenda.[11]

Disquiet at the changes has thus not completely escaped the attention of the government. At an August 2023 meeting of the National Assembly’s Committee on Defense and Security, Lưu Văn Đức, a member of the Ethnic Council, observed that members of the public had raised “concerns” (băn khoăn) about the removal of dân tộc and religion. Yet, while he concluded that this demonstrated a need for better communication and explanation of the issue, no reference was made to what precisely should be communicated or explained.[12] A clear articulation of the reasons behind the reforms — let alone one capable of rebutting accusations of assimilationism — thus remains elusive.

Ethnicity and the state

The Vietnamese government’s apparent satisfaction with an at-best-partially transparent approach to its new regulations is consistent with a long statist history of the whole notion of dân tộc. The category’s positioning on the reverse of the old paper CMND alongside physiological characteristics such as fingerprints and details of the bearer’s distinguishing features, rather than on the front with their name, place of registration and date of birth, belies its status as a matter whose parameters have lain firmly within the purview of the state. As anthropologist Itō Masako notes in a study of the history of ethnic classification in Vietnam, this has been the case ever since the Communist Party, drawing on Soviet and Chinese examples, undertook to identify and classify dân tộc during the 1950s: “Vietnam’s ethnology aimed to serve the political goal of national integration from the start,” she writes; “ethnology was inseparable from politics in Vietnam.”[13] Given this, we should thus perhaps not be surprised that the new card keeps ethnicity locked behind a QR code which is only accessible to certain state officials, and mostly privileges the state’s sense of what is “sensitive” and “convenient.”

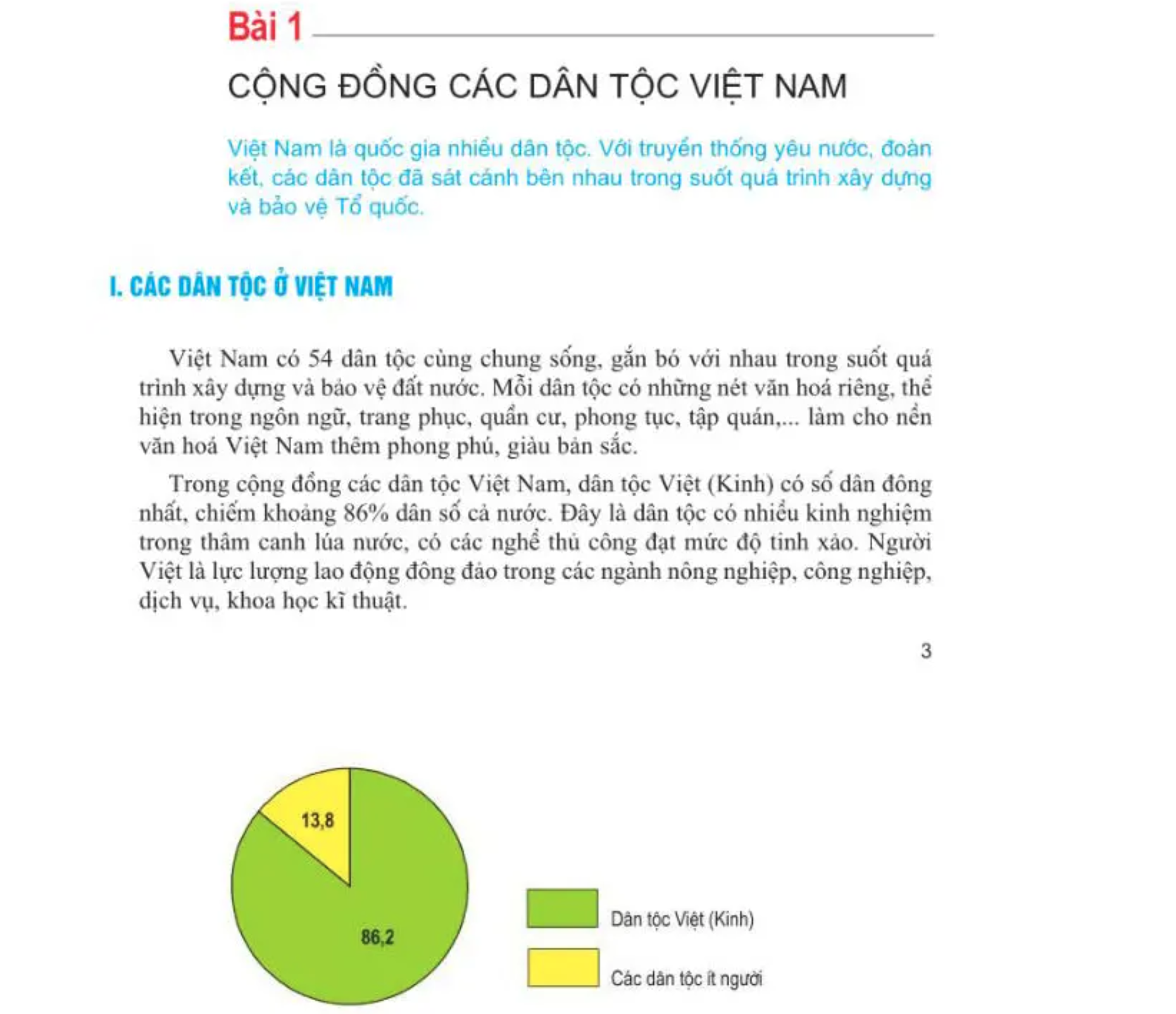

Yet if the reforms are intended to make ethnic identity a less public idea, this appears to undercut continuing vocal promotion of Vietnam as a country comprising fifty-four “ethnic communities” (54 dân tộc) across numerous domains of state-subjectivity. Mentions of “54 dân tộc” appear throughout history and geography textbooks from primary to high school.[14] In fifth grade pupils learn that Vietnam’s fifty-four ethnic minorities, defined as “anh em” (siblings), live in a close-knit community with a shared origin. The elevated position of the majority Kinh people is justified to ninth graders on the basis of their role as “anh cả” (the eldest brother) in the Vietnamese family (Image 2).[15] Twelfth-grade textbooks acknowledge unbalanced economic development between ethnic groups, but emphasize that the government is making efforts to improve these underprivileged communities' living standards and economic conditions.

Educational and research agendas at tertiary institutions have also been trained on Vietnam’s minority communities, including in response to government policy.[16] For example, an official emphasis on the cultural value of ethnic diversity has been reflected in the academic programming of Vietnam National University as one of its eight most important research fields for 2015-2030.[17] Culture is now inscribed as a core issue within the government’s overall strategy vis-à-vis ethnic minorities.[18]

In the tourism sector too, ethnic tourism ranks high among national development priorities. Increasingly popular itineraries take visitors out of major urban centers to the karst and paddy lands of the north, the western highlands, and the Mekong Delta. Overnight trains from Hanoi ferry thousands of tourists to Sa Pa in Lào Cai province where well established “ethnic tourism” experiences include homestays and treks with hosts and guides from among local Hmong, Dao, and Giáy communities. In Cao Bằng province, six hours north of Hanoi along the border with China, a recent push for eco-travel promotes the natural wonders of a UNESCO-backed geo-park, sites from Vietnam’s socialist revolution, and “craft villages” offering encounters with indigenous Nùng and Tày people . While private businesses have driven much of this, provincial authorities are closely involved in marketing local ethnic assets. As the official government newspaper Báo Cao Bằng observed in a 2023 tourism article, the province is “rich in the harmony between identities of many fraternal ethnic groups.”[19] Deploying evocative descriptions of clear waters and rice paddies, the article promotes the region’s “unique ethnic cultural values” and “diversity” (đa dạng).

Such campaigns address a clientele receptive to the popular idea that ethnic minority people are encountered primarily in picturesque natural surrounds. Vietnam is moreover not the only reformed socialist state where ethnicity and rurality elide to meet market demand, for as anthropologist Jenny Chio shows in her fieldwork in a Zhuang community just over Cao Bằng’s border with Guangxi province, China, development of a local tourist industry includes strenuous efforts to maintain an authentically bucolic “ethnic” look for villages despite the pollution and urbanization that development brings to the area.[20]

Hanoi-based tourists need not travel far for comparable experiences. Forty or so kilometers outside the capital, the Vietnam Ethnic Culture and Tourism Village (Làng Văn hóa - Du lịch các dân tộc Việt Nam) markets the party state’s own idea of dân tộc even more directly - including to visitors guided by our interlocutor Thanh. With a grand entrance displaying the legend “54 dân tộc Việt Nam” and an outline of the s-shaped national map in the colours of the state flag, the vast park complex offers a condensed simulation of the country’s idealised ethnic tapestry (Image 3). As tourists are shuttled on 12-seater electric buggies between 54 distinct “villages” staffed and inhabited full-time by representatives of the relevant groups, it is the politically appropriate categories and no others which are commodities for tourist consumption (Images 4 and 5).

Ethnological repercussions

Clearly the removal of ethnicity from identity cards has not made organic diversity disappear overnight. As inclusion of overseas Việt kiều in the new card regime shows, the Vietnamese state is hardly beyond mobilizing ethnicity to buttress its projects. Yet those unsure about or opposed to the change are not wrong in observing that the reforms alter the terms on which ethnicity exists within the Vietnamese party-state. It is not ethnicity itself that is under threat, but the specific notion of dân tộc as it has figured in Vietnamese social and political life for the past seventy years. Digitization and use of biometrics in public administration, as well as certain concerns around privacy and data protection, are widespread global phenomena, but in the context of Vietnam as a multiethnic socialist state, these carry a particular valence.

From the time of the country’s hard-won independence, Vietnam’s ethnic classification programme represented a core tenet of the construction of a new state, indeed a new kind of state, emerging from experiences of French colonialism and - further back in time - inclusion within a China-centred regional order. Decolonial objectives were common to comparable projects in other state socialist contexts. In the Soviet Union from the 1920s, followed by the People’s Republic of China from the 1950s, the work of Communist Party-backed ethnologists travelling to remote areas and identifying and codifying the languages, costumes, cuisines, festivals and other “ethnic” characteristics of the people that lived there was pivotal in demonstrating to diverse populations that new revolutionary orders had a place for them. Consequently, however much Marxist theory might have predicted the ultimate disappearance of ethnic divides under Communism, socialist states have tended to become very attached to the ethnic paradigms key to the constitution of the polity. This has made reform a sensitive issue everywhere. It took the collapse of the USSR to trigger a reappraisal of the idea of Soviet “nationality” (natsional’nost’) which was removed from Russian passports in the 1990s, and survives in a variety of forms in the other states of the former Union. In China, debates over an official transition to a “second-generation ethnic policy” (di’er dai minzu zhengce) more focused on inter-group “blending” (jiaorong) are already over a decade old, but for now the minzu category remains a stubbornly persistent feature of the PRC ID card (shenfenzheng).

Indeed, recent reforms are not the first time that the countervailing forces of celebrating categorical diversity while stressing national unity have produced curious paradoxes in Vietnam. In her investigation of government efforts to save the Ơ-Đu people of Nghệ An Province, Vietnam’s smallest minority, from complete assimilation, Itō Masako asked local experts why, given that Marxist and Stalinist theory both claim that ethnicity will ultimately melt away, is it such a problem that a group like the Ơ-Đu might disappear? The issue, she was told, is that state officials and Vietnamese scholars have spent so long saying that Vietnam is a state consisting of fifty-four ethnic groups that it would be a politically unacceptable sign of negligence if one of these groups ceased to exist.[21] Identity card changes and responses to them thus only underscore further how difficult it is to walk back codified socialist visions of ethnicity once everyone has bought into them, whether as loci of self-identification or as pivots for citizens in their dealings with the state.

Our research thus reveals a party-state which is well aware of the pitfalls of its new measures attempting to navigate senses of self on different scales, ranging from individual citizens to the state itself. Given anthropologists’ interest in subjectivity and the centrality of ethnology as an applied practice to these transformations, our observations touch on numerous themes of relevance to researchers working on minority communities, development, and everyday politics in Vietnam and elsewhere. In the long afterlife of twentieth-century state socialist projects to construct ethnicity, and in a part of the world whose importance is likely only to increase in years to come, exploring these issues is critical for understanding diversity and identity, beyond Euro-American multiculturalism.

Notes:

[1] Lê Hà. 2024. “Hành trình “về đích” cấp căn cước cho trẻ em.” Báo điện tử - Đảng Cộng sản Việt Nam 16 August 2024. Available at: https://dangcongsan.vn/tam-nhin-moi-muc-tieu-moi-phat-trien-6-vung-chien-luoc/trung-du-va-mien-nui-bac-bo/hanh-trinh-ve-dich-cap-can-cuoc-cho-tre-em-675192.html (accessed 20 February 2025).

[2] Quốc Hội Cộng Hòa Xã Hội Chủ Nghĩa Viẹt Nam. 2023. “Luật Căn Cước (Luật số: 26/2023/QH15).” Thư Viện Pháp Luật 27 November 2023. Available at: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Quyen-dan-su/Luat-Can-cuoc-26-2023-QH15-552422.aspx (accessed 20 February 2025); see Article 18, Clause 2.

[3] Trọng Phụng. 2024. “Timeline: Lịch sử đổi thẻ căn cước ở Việt Nam.” Tạp chí Luật Khoa 19 April 2024. Available at: https://www.luatkhoa.com/2024/04/dan-sap-bi-thu-thap-mong-mat-nhin-lai-cac-lan-doi-can-cuoc-kieu-den-cu/ (accessed 20 February 2025).

[4] A person’s fingerprints, retina and face scans, voice signature, and DNA record are also linked to the new cards.

[5] Some explanation has been offered by the Ministry of Public Security (Bộ Công an) relating to residency information. See Nước Nước. 2024. “Từ 1/7: Thông tin nơi cư trú trên thẻ căn cước sẽ ghi nơi thường trú.” Báo Điện tử Chính phủ 25 June 2024. Available at: https://baochinhphu.vn/tu-1-7-thong-tin-noi-cu-tru-tren-the-can-cuoc-se-ghi-noi-thuong-tru-102240625110901626.htm (accessed 20 February 2025).

[6] Government of Vietnam. 2023. “Decree on Protection of Personal Data (No. 13/2023/ND-CP).” Thư Viện Pháp Luật 17 April 2023. Available at:https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/EN/Cong-nghe-thong-tin/Decree-No-13-2023-ND-CP-dated-April-17-2023-on-protection-of-personal-data/564343/tieng-anh.aspx (accessed 20 February 2025).

[7] Học viện Chính trị Công an Nhân dân - Bộ Công an. 2023. “Ở Việt Nam các dân tộc đều bình đẳng, không ai bị bỏ lại phía sau.” Bocongan.gov.vn 10 September 2023. Available at:https://hvctcand.bocongan.gov.vn/chong-dien-bien-hoa-binh/o-viet-nam-cac-dan-toc-deu-binh-dang-khong-ai-bi-bo-lai-phia-sau-5559 (accessed 20 February 2025).

[8] Hoài Thu. 2023. “Quốc hội sẽ chốt những thông tin được tích hợp vào thẻ căn cước.” Dân Trí 27 November 2023. Available at: https://dantri.com.vn/xa-hoi/quoc-hoi-se-chot-nhung-thong-tin-duoc-tich-hop-vao-the-can-cuoc-20231126142423210.htm (accessed 25 August 2025).

[9] CAND. 2023. “Bộ trưởng Tô Lâm: Căn cước công dân không thể theo dõi người dân!” Cổng thông tin điện tử Công an Hà Tĩnh 10 June 2023. Available at: https://congan.hatinh.gov.vn/bai-viet/bo-truong-to-lam-can-cuoc-cong-dan-khong-the-theo-doi-nguoi-dan_1686379037.caht, (accessed 25 August 2025).

[10] Anonymous. 2022. “Đối với thông tin cá nhân trong cơ sở dữ liệu quốc gia về dân cư có thể hiện dân tộc hay không?” Hỏi Đáp Pháp Luật 19 August 2022. Available at: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/hoi-dap-phap-luat/5B01F-hd-thong-tin-ca-nhan-trong-co-so-du-lieu-quoc-gia-ve-dan-cu-co-the-hien-dan-toc-khong.html (accessed 20 February 2025).

[11] Thanh Vàng. No date. “Không để các thế lực thù địch lợi dung việc cấp CCCD, xuyên tạc chia rẽ dân tộc.” Công an Tỉnh Vĩnh Long. Available at: https://congan.vinhlong.gov.vn/tin-tuc/-/journal_content/56_INSTANCE_sJaRkI9m9m1g/10180/1762917 (accessed 20 February 2025).

[12] Thành Chung. 2023. “Băn khoăn đề xuất bỏ dân tộc, tôn giáo trên căn cước mới.” Tuổi Trẻ 10 August 2023.Available at: https://tuoitre.vn/ban-khoan-de-xuat-bo-dan-toc-ton-giao-tren-can-cuoc-moi-20230810180820042.htm (accessed 20 February 2025).

[13] Itō Masako. 2013. Politics of Ethnic Classification in Vietnam (trans. Minako Sato). Kyoto University Press, p. 179.

[14] Nguyễn Dược (Tổng chủ biên). 2014. Địa Lý 9. Bộ Giáo Dục và Đào Tạo, Nhà Xuất Bản Giáo Dục Việt Nam, p.4. Image 3 comes from an edition of a single set of geography textbooks used across Vietnam until 2020. Since that year schools may now choose between three sets of textbooks from different publishers. The new editions of the ninth-grade book do not include the pie chart on the illustration here, but all continue to refer to the 54 ethnic groups.

[15] Oscar Salemink. 2003. The Ethnography of Vietnam's Central Highlanders: A Historical Contextualization, 1850–1990. University of Hawaii Press, p.147.

[16] Nguyễn Thị Song Sà. 2023. “Chính sách bảo tồn và phát huy giá trị văn hóa các dân tộc thiểu số ở Việt Nam.”Tạp chí Cộng sản 12 August 2023. Available at:https://www.tapchicongsan.org.vn/web/guest/van_hoa_xa_hoi/-/2018/828114/chinh-sach-bao-ton-va-phat-huy-gia-tri-van-hoa-cac-dan-toc-thieu-so-o-viet-nam.aspx (accessed 20 February 2025).

[17] Vietnam National University. 2024. Chương trình KH&CN trọng điểm cấp ĐHQGHN. Available at:http://science.vnu.edu.vn/2024/12/16/ct-khcn-trong-diem-cap-dhqghn-uu-tien-trien-khai-nam-2025/ (accessed 20 February 2025).

[18] Party Resolution No. 4 of the 13th Central Committee announced in January 2021, available at: https://baochinhphu.vn/toan-van-nghi-quyet-dai-hoi-dai-bieu-toan-quoc-lan-thu-xiii-cua-dang-102288263.htm (accessed 20 February 2025).

[19] Minh Hòa. 2023. “Giá trị văn hóa dân tộc độc đáo của non nước Cao Bằng.” Báo Cao Bằng 22 March 2023. Available at: https://baocaobang.vn/-5390.html (accessed 20 February 2025).

[20] Chio, Jenny. 2014. A Landscape of Travel: The Work of Tourism in Rural Ethnic China. University of Washington Press, pp. 24-25.

[21] Itō. 2013. pp. 158-159.

Ed Pulford is an Anthropologist and Senior Lecturer in Chinese Studies at the University of Manchester. His research and teaching focus on past and present experiences of socialism and empire in Eurasia, including along the China-Russia border where his first two books Mirrorlands (2019) and Past Progress (2024) examine ideas of time, friendship and identity. His current project explores differing practices of ethnic classification in various state socialist contexts.

Trần Mai Hương is a PhD student in Anthropology at the Faculty of Anthropology and Religious Studies, University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vietnam National University, Hanoi. Her research focuses on youth-led urban-to-rural migration in Vietnam and East Asia. With academic training in Japan and China, her research examines how such migrations are embedded in broader societal transformations in the region through a comparative approach.

To cite this essay, please use the bibliographic entry suggested below:

Ed Pulford and Trần Mai Hương, “Socialist State Subjectivity: The Changing Stakes of Vietnam’s Ethnic Classification Policy,” criticalasianstudies.org Commentary Board, November 7, 2025. https://doi.org/10.52698/UHGY5957.