Special Series: “New Directions in Africa-China Studies” | Zixi Zhao, "Replacing the Bad Birds": China's Domestic Industrial Upgrade and its Implications for China-Africa Relations

Introduction

Last summer, I was talking to an interlocutor who helped connect me with a factory in Shenzhen where I was conducting fieldwork. The factory had, some years back, relocated from its original location nearer the city center to a remote industrial park. My interlocutor and I were discussing how many factories in Shenzhen, it seemed, had moved – or been pushed – further into the city’s outskirts, or, in some cases, to nearby satellite cities. In this context, he told me about Chen.

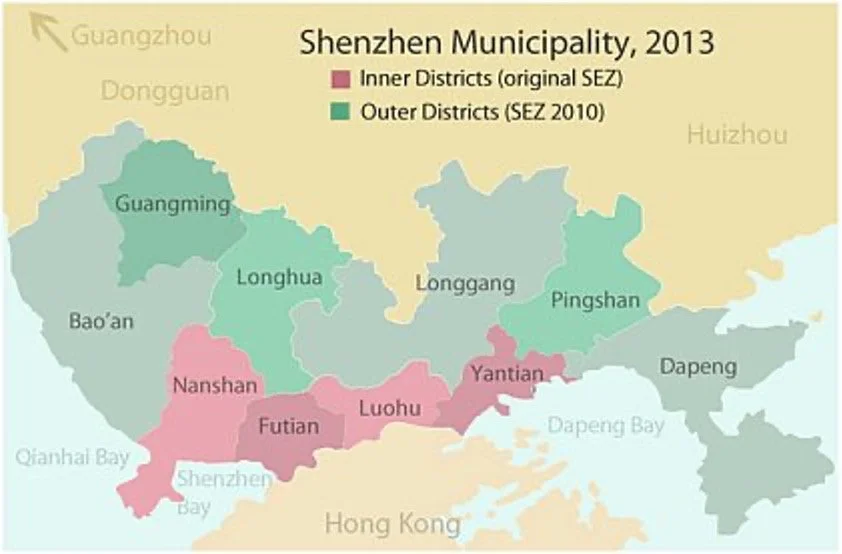

Chen owned a mid-sized electronics factory in Dongguan, a manufacturing hub neighboring Shenzhen (see Figure 1), that produces components for the low-end phone market. In 2012, Dongguan began cracking down on factories that failed to meet its new ideal of “green, sustainable production.” By 2019, over fifty thousand enterprises had been cleared from the city, Chen’s among them (Zhou 2019). After a momentary reprieve through bureaucratic maneuvering, his factory collapsed in 2020. Looking for an alternative opportunity, Chen saw Africa. In 2021, Chen’s factory was reborn in Lagos, Nigeria.

The Notes from the Field collection, of which this essay is a part, suggests that there has been a shift in Chinese engagements in Africa, from large-scale, state-led investments in infrastructure to a mode where private industry is taking a dominant role. Chen’s relocation of his factory to Lagos illustrates that the rise of Chinese private industry in Africa is not simply a matter of adventurous Chinese entrepreneurs seeking out new opportunities at a global frontier of capital. It is also that these entrepreneurs are propelled by conditions at home in China – conditions comprised of both market forces and the state’s economic goals and policies.

Put simply, the Chinese government has been encouraging a shift at home towards high-end, high-tech industry and Chinese-led innovation. In cities like Shenzhen and Guangzhou, hubs of manufacturing and trade, ground-level policies and incentives encourage the newly-prioritized high-tech industries and make it harder for older industries to survive. In this environment, factory owners in the now-deprioritized industries are forced to look abroad for a more favorable climate in which to set up shop.

In a certain sense, however, the policies that create these conditions are nothing new. Since the reform and opening up movement of 1979, the government has encouraged industrial and technological development and set policy to incentivize private industry to pursue these goals. Also, since 1979, these policies have had a spatial – or spatiotemporal – character: newer industries are given priority space in cities’ central districts, and older industries are displaced to the outskirts. What is new here is that deprioritized industries are not just moving further into the rural/urban periphery, or to second-tier, satellite cities (as sometimes happens), but outside of China entirely – to Africa and elsewhere.

Taking Shenzhen as a paradigmatic example, this essay presents an overview of Chinese economic goals and how they have played out in industrial policy from 1979 to the present. As I aim to show, as the Chinese economy and technological capacity grow, and as cities expand in tandem, emerging industries are always given space at the center, while the older, deprioritized industries are pushed further afield – ultimately leading to conditions where Chen and many manufacturers like him move overseas. I conclude by reflecting on how these domestic conditions relate to China’s current engagements with Africa, and what this recent shift may mean for the future.

Kicking off the Reform: 1979 - 1991

Figure 1. Administration Map of Shenzhen Municipality in 2013. Districts shaded in pink were the original area of the SEZ. Districts shaded in green are other areas of Shenzhen outside of the SEZ. Dongguan (neighboring city) is located in the Northwest, while Huizhou (neighboring city) is in the Northeast. Map extracted from O'Donnell 2013.

In 1980, Shenzhen was chosen as one of four cities in China to launch the country’s market reforms. With its proximity to Hong Kong and the access to global markets that proximity entails, Shenzhen was slated for development into a global manufacturing hub. The city’s southern coastal areas (consisting of Nanshan, Futian, Luohu, and Yantian districts as shown in Figure 1) – where the city borders Hong Kong– were designated as Special Economic Zones (SEZs) to house the new, private industry which would kickstart the nation’s transition to a market economy.

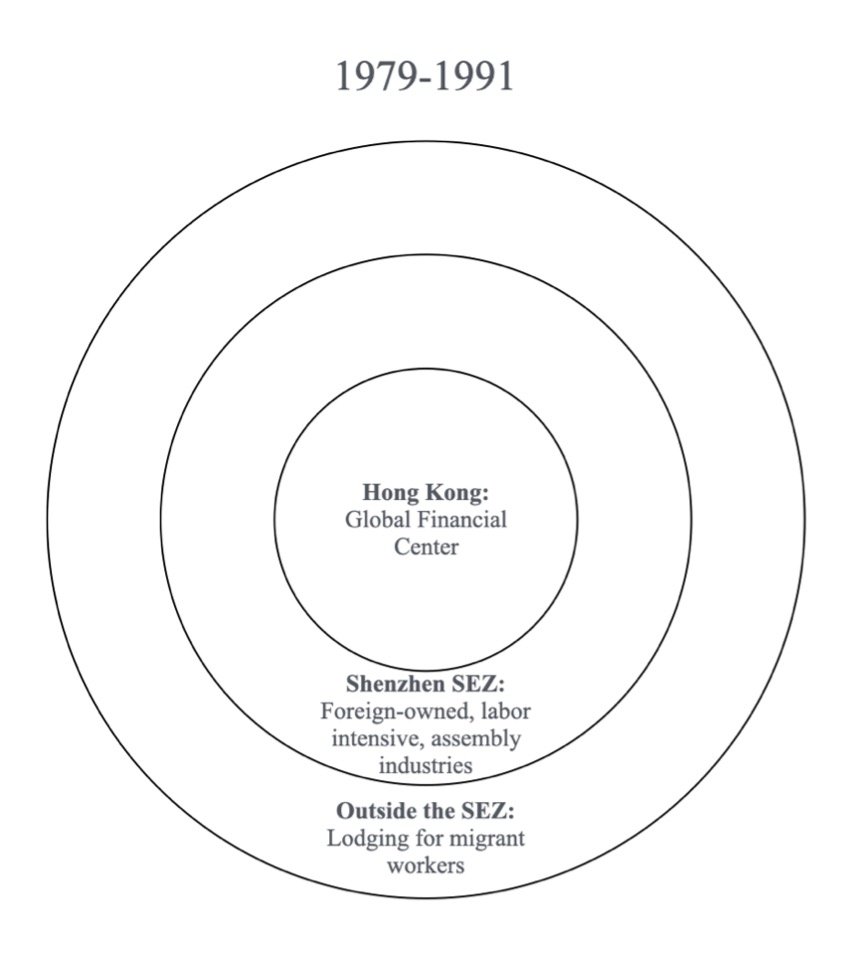

Following this designation, the spatial composition of Shenzhen was marked by a “second line border” (erxianguan) consisting of barbed wire fencing that divided the city into areas inside and outside the SEZ (the “first line border” being that which separated the city from Hong Kong) (see Figure 2). The two areas were governed with different economic and social policies, though both played a key role in Shenzhen’s new economic system. The area within the SEZ housed private factories, while the areas outside the SEZ held lodging for migrant laborers (see Figure 3) (Blackwell and Ma 2017, 130).

At the start of the Reform, factories within the SEZ were mainly dedicated to basic assembly: textiles, garments, plastics, toys, and basic electronic components. By the mid-eighties, this advanced to basic electronics like television and radio, and, by the late-eighties, computer parts. These factories were at the frontier of China’s nascent industries, especially compared to regions outside of the SEZs.

Nonetheless, in this period between 1979 and 1991, Shenzhen’s mode of production was under what was called the “three imports and one incentive” model – foreign-owned factories producing with foreign-supplied materials, samples, and equipment (the three imports) and incentive policies from the SEZ government (one incentive) (Shenzhen Municipal Archives 2023). The only domestic inputs in this mode were labor and land. In other words, most of the production in Shenzhen was labor-intensive, assembling low-cost components for the global north, with materials, equipment, and expertise also supplied by the global north.

For the government guiding China’s transition to a market economy, this presented a problem: total reliance on foreign firms, without knowledge transfer and capacity building, would leave China stuck in this lower position on the global supply chain. This led to the government’s policy response, which I will illustrate in the following section.

Figure 2. A map of Shenzhen that outlines the "first line border" in brown color (the SZ-HK Border) and the "second line border" in red. Map extracted from Wilson 2019.

Figure 3. Envisioned industrial composition in state economic policies from 1979 to 1991. Figure created by the author.

A spatially discrepant upgrade: 1991-2008

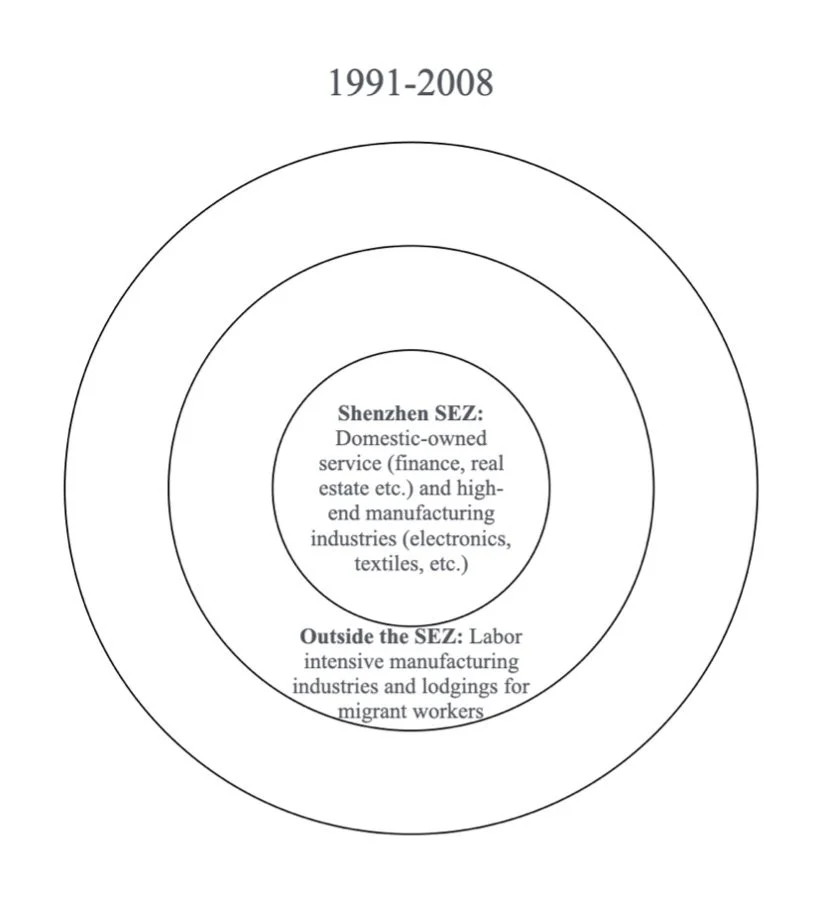

Twelve years into the era of market reforms, the municipal government of Shenzhen released the 1991 Ten-Year Scheme and Five-Year Plan, the municipal blueprint for economic and social development (Zheng 1991). The plan stressed the need for an “industrial upgrade,” reasoning that labor-intensive manufacturing required more land, energy, and civil services than the value added they produce (Zheng 1991). Instead, it advocated for new, more advanced industries and manufacturing processes alongside the development of the service sector.

Importantly, what the government meant by “more advanced” manufacturing was determined by a combination of factors, including the technological advancement of production equipment and methods, pollution, energy use, labor costs, the use of local inputs, decreased reliance on foreign guidance, and volume, speed, and quality of output (Zheng 1991). The primary industries that developed in this period were, on the whole, more advanced than the previous ones – advanced electronics, IT, logistics, and finance. Ultimately, however, the underlying goal was not only about the industries themselves, but also about knowledge transfer and increasing Chinese expertise and capacity.

This “industrial upgrade,” however, was applied only to the SEZ. Meanwhile, the more rural districts surrounding the SEZ were slated for industrial development on a different plan. Outside the SEZ, the government prioritized the same low-end manufacturing industries previously encouraged within. In fact, a policy document from 1993 (Lai 2020) advocated for Longgang, a large district neighboring the SEZ, to develop following the aforementioned “three imports and one incentive” model, the very model that was explicitly considered as “in-need of transformation” for the SEZ in the 1991 plan (Lai 2020; Zheng 1991). In this way, Longgang and other neighboring districts became the new home for low-end manufacturing industries that were increasingly discouraged within the SEZ. This period of upgrade resulted in the industrial composition presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Envisioned industrial composition in state economic policies from 1991 to 2008. Figure created by the author.

Reforming under crisis: 2008-2015

While Shenzhen’s first wave of industrial upgrade occurred in the 1990s and 2000s, the 2008 financial crisis marked a significant acceleration of the process. As the crisis began in the US and quickly spread to Europe, China’s two main export markets, Chinese manufacturers were hit hard (Huang and Yang 2009). The crisis demanded an urgent state response and realignment of economic policy. The resulting plan aimed to reduce the country’s reliance on foreign exports, while strengthening domestic markets, largely through civil infrastructure projects and real estate (www.gov.cn 2008a). At the same time, for Chinese policy-makers, it highlighted the urgency of improving manufacturing into higher-tech, higher value industries, while strengthening Chinese innovation – a long-held goal, but one which had proceeded more slowly than the state would have liked.

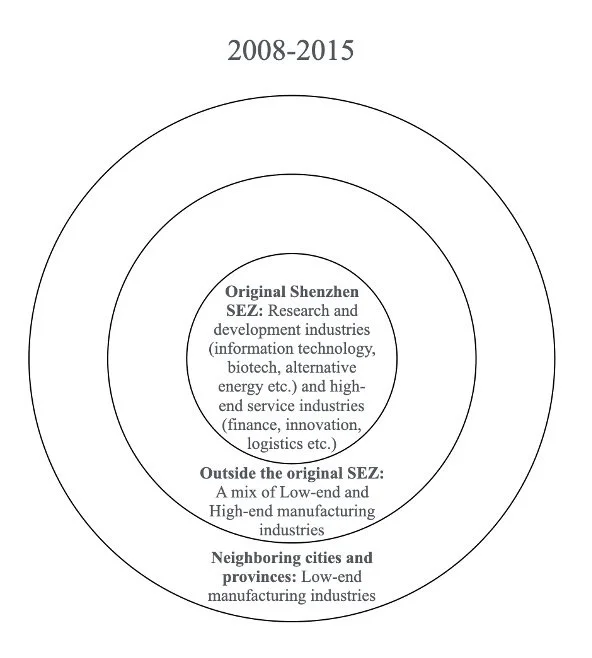

In Guangdong (the home province of Shenzhen), these objectives were materialized through what was popularly called the “empty the cage and replace the birds” movement (tenglonghuanniao). It sought to empty the “bad birds” (deprioritized industries) from the cage (the precious land and resources of the Delta) and replace them with “good birds” (newly-prioritized, technologically advanced industries) (www.gov.cn 2008b). Its operating principles were outlined in guidelines published by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) (NDRC 2015). The guideline describes a tripartite system of categorization that ranks industries and firms into three tiers – encouraged, restricted, and obsolete – based on technological advancement, ecological sustainability, safety, legality, and contribution to society. Different policies were applied to firms in different tiers, aiming to, as their names suggest, encourage, restrict, and make them obsolete.

Firms in the encouraged tier were offered expedited registration, tax cuts, and government-backed loans (NDRC 2023, 10, 84). Meanwhile, banks and firms were banned from investing in or issuing loans to firms in the obsolete tiers. They were given a set period to remove their obsolete components — techniques, equipment, products. Failing to do so led to forced shutdowns, revocation of permits, and power shut-offs (NDRC 2023, 107). Most low-end, labor-intensive manufacturing factories fell under the restricted and obsolete tiers.

Under this rubric and the severe economic conditions of the crisis, the state cleared the undesirable industries by declining to offer bailouts to manufacturers. Wang Yang, the Party Secretary of Guangdong at the time, commented that with bankruptcy and unemployment, “the financial crisis had achieved something the government wanted to achieve but was unable to,” and that “the country will not spend the effort to save backwards industries” (Southcn.com 2008).

Moreover, alongside increasing urbanization and gentrification, the policies of industrial upgrade (e.g., the spatial redistribution of industries in the Bird Movement) have pushed up land, rents, energy, and labor costs in the city center by introducing high-end industries and auxiliaries. Such an environment makes it impossible for low-end manufacturers that were already struggling under the direct discouragement from the government to survive. Hence, they had to relocate spatially to more remote areas where the costs were lower.

Those located within the SEZ, where the policies were applied the most rigidly – mostly factories that emerged before 1991 but clung to the SEZ in the first wave – had to leave or close, while those without were economically sabotaged by constant inspections and financial restrictions – a long-term pressure that signaled eventual displacement.

Spatially, the “good birds” were to occupy the major parts of the SEZ. These were development and research centers of high-tech, strategic industries such as information technology, biotech, and alternative energy, and high-end service industries like finance, innovative design, and logistics (Shenzhen Bureau Of Statistics 2011). Outside the SEZ, there is a mix of manufacturing complexes of high-tech industries, whose research centers are located within the SEZ, and low-end, labor-intensive factories displaced from within. In the upcoming years, these factories were further pushed outward into the periphery of Shenzhen and eventually to the neighboring cities and provinces (as demonstrated in Figure 5). For instance, a garment factory in an urban village within the SEZ, where I conducted fieldwork, was first displaced outside the SEZ and then to the neighboring city of Dongguan.

Figure 5. Envisioned industrial composition in state economic policies from 2008 to 2015. Figure created by the author.

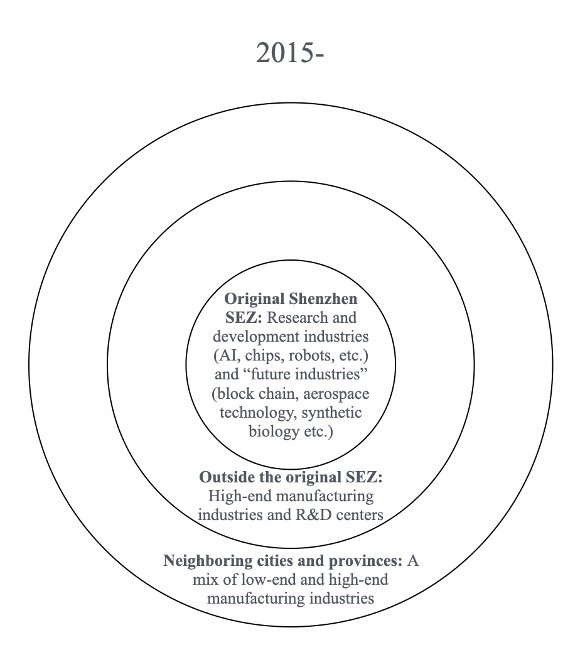

Beyond “Made in China”: 2015 – Present

In 2015, the Chinese government launched a new set of economic reforms (State Council of the PRC 2015; Xinhuanet 2025b). In many ways, they were a continuation of previous themes: offloading obsolete industries, while prioritizing quality, efficiency, and Chinese expertise and capacity in manufacturing to move up the global supply chain. Where the 2015 vision differed from its predecessors is that it set the goal of making China one of the global leaders of technological innovation, high-tech manufacturing and development. This vision was popularly glossed as a shift from “Made in China” to “Create in China” and “Made in China intelligently” (www.gov.cn 2016; State Council of the PRC 2015).

In practice, this meant prioritizing new, strategic industries: semiconductors, electric vehicles, AI, robotics, telecommunications, biomedicine, renewable energy, fintech, e-commerce infrastructure. Like previously, these goals were accompanied by a constellation of policies to incentivize investment in new industries and disincentivize those now considered obsolete. This latest upgrade continued on these terms until the COVID pandemic hit in 2019.

For many manufacturers, particularly those in industries no longer prioritized in the 2015 plan, the pandemic marks a similar moment to the 2008 financial crisis. The economic downturn caused by the pandemic was joined by pandemic-related restrictions: mass testing, mandated lockdowns, quarantines, and tightened customs controls. Moreover, just as they had in 2008, the government used the pandemic crisis to accelerate its industrial and economic goals. As reflected by my interlocutors from a factory in Shenzhen, while protections, assistance, and special waivers and dispensations were offered to prioritized industries, manufacturers in deprioritized industries were left to the impacts of pandemic-related economic conditions.

As a result, further spatial diffusion started taking place in Shenzhen (see Figure 6). With the expansion of the SEZ to cover all of Shenzhen in 2010 and the official decommission of the “second-line border” in 2018, Longgang and other regions that used to be outside of the SEZ were set to be developed into major CBDs housing high-end manufacturing industries (China News Service 2018). This is highlighted in the 2022 20+8 industrial layout of Shenzhen, a key policy paper that envisions 20 advanced manufacturing parks that will spread across what used to be regions outside the SEZ (see Figure 7) (China Development Institute 2022). Low-end, labor-intensive industries are no longer included in the spatial composition.

Low-end manufacturing factories are also being pushed out from the smaller, satellite cities to which many moved during the 2008 period. Dongguan, for example, started industrial upgrades of its own in the 2010s, aiming for more sustainable and automated modes of manufacturing (Dongguan Municipal People’s Government 2014). Chen’s story of displacement occurred in this context, wherein one who had established their factory in Dongguan due to the industrial transformation in Shenzhen was later faced with a similar movement in Dongguan.

As more and more urban regions turned to industrial upgrade, rural areas became an option for relocation. However, since 2017, “Rural Revitalizations” have been steering the rural areas toward their own ideals of a modernized future surrounding high-tech food production, environmental and cultural protection, and innovative education and entrepreneurship (Xinhuanet 2025a). The displaced industries from urban areas also don’t fit Chinese rural futures.

Figure 6. Envisioned industrial composition in state economic policies from 2015 onward. Figure created by the author.

Figure 7. A map of the twenty advanced manufacturing parks outlined in the 2022 20+8 plan. Map extracted from China Development Institute 2022.

China-Africa

As I’ve argued here, China’s rise up the global supply chain from low-end to high-tech manufacturing followed a distinct spatial pattern in which newer industries were given priority in the centers of China’s major manufacturing cities, and, through a combination of government policy and market forces, older industries pushed further out. Over time, and as cities expanded, older industries were pushed further into the periphery or to second-tier satellite cities. At present, the current set of policy goals – including a new vision for rural China – is pushing many of the lowest-end manufacturers outside of China entirely.

What does all this tell us about China-Africa engagements? First, my aim was to suggest that the paradigm shift we explore in this special collection – from a state-to-state mode of engagement to one dominated by private investment and Chinese entrepreneurship – is not occurring in a vacuum. Many Chinese entrepreneurs, like Chen, are not only offshoring to Africa in search of cheaper labor and a favorable business environment, but also doing so in response to market and policy conditions back home. In other words, as scholars debate the nature of China-Africa engagements, or other international engagements, we need to look beyond or “below” geopolitical strategy and examine how domestic conditions and policy goals, intentionally or otherwise, are a part of the equation.

The same is true in reverse. After the 2008 crisis, when China pivoted to domestic infrastructure and real estate development to counterbalance its loss in exports, the ports, roads, railroads, electricity grids, and other megaprojects characteristic of the earlier state-to-state mode of Chinese investments in Africa were essential to the process. It was through these ports, roads, and railroads that extractive industries (also largely Chinese-owned) were able to export the raw materials that fueled the large-scale construction projects that pulled China out of the crisis (Shu 2012).

Now, in the current era, these same ports, roads, and railroads are serving a new purpose. In the current domestic climate, Chinese manufacturers are offshoring not only to Africa but also to Latin America, Southeast Asia, etc. In this way, Chinese-built megaprojects (along with lower labor costs) are part of what makes Africa a viable destination for Chinese manufacturers to set up shop. They provide essential logistics and transportation infrastructure that allow them to produce for export markets, whether in other African countries, back home to China, or elsewhere.

If my general thesis about Chinese domestic policy and private offshoring holds true, there could be further implications. At the current moment, Chinese manufacturing in Africa is primarily confined to textiles, electronic components, and other bottom-of-the-supply-chain industries characteristic of China’s first twelve years in its market transition, and now deemed obsolete and undesirable by the government. In the future, however, as Chinese industrial and economic goals continue to evolve, they may well serve as a bellwether for what offshored industries turn up in Africa. Moreover, it is likely that such industries will feed and cater to the many digital initiatives that are underway across the African continent today (Pollio 2025).

References

China Development Institute. 2022. “深圳‘20+8’产业布局锚定1.5万亿元产业蓝海 [Shenzhen’s ‘20+8’ Industrial Layout Targets a 1.5 Trillion Yuan Blue Ocean of Industries].” June 13. http://www.cdi.com.cn/Article/Detail/17872.

China News Service. 2018. “国务院批复:同意撤销深圳经济特区管理线 [The State Council Approved the Abolition of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone Management Line].” January 15. https://www.chinanews.com/gn/2018/01-15/8424483.shtml.

Dongguan Municipal People’s Government. 2014. “关于印发《东莞市推进企业‘机器换人’行动计划(2014-2016年)》的通知 [Notice Regarding the Issuance of the ‘Dongguan City Action Plan for Promoting “Machine Replacement” in Enterprises (2014-2016)’].” August 11. https://www.dg.gov.cn/zwgk/zfgb/szfbgswj/content/post_353845.html.

Huang, Chaohan, and Mu Yang. 2009. “2009年中国经济面临急剧下降的危机 [China’s Economy Faced a Crisis of Sharp Decline in 2009].” Vol. 67. NUS East Asian Institute - Singapore.

Lai, Limin. 2020. “深圳龙岗‘大工业’的行动指南 [Action Guide for Shenzhen Longgang’s ‘Big Industry’].” September 29. https://digi.shenchuang.com/20200929/1561348.shtml.

Ma, Emma Xin, and Adrian Blackwell. 2017. “The Political Architecture of the First and Second Lines.” In Learning from Shenzhen: China’s Post-Mao Experiment from Special Zone to Model City, edited by Mary Ann O’Donnell, Winnie Wong, and Jonathan Bach. University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226401263.003.0007.

National Development and Reform Commission. 2005. “产业结构调整指导目录(2005年本) [Guidance Catalogue for Industrial Structure Adjustment (2005 Edition)].” December 2. https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/fzggwl/200512/t20051222_960679.html.

National Development and Reform Commission. 2023. “产业结构调整指导目录(2024年本) [Guidance Catalogue for Industrial Structure Adjustment (2024 Edition)].” December 1. https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/fzggwl/200512/t20051222_960679.html.

O’Donnell, Mary Ann. 2013. “Laying Siege to the Villages: Lessons from Shenzhen.” openDemocracy, March 28. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opensecurity/laying-siege-to-villages-lessons-from-shenzhen/.

Pollio, Andrea. 2026. Silicon Elsewhere: Nairobi, Global China, and the Promise of Techno-Capital. University of California Press.

Shenzhen Bureau Of Statistics. 2011. “深圳市2010年国民经济和社会发展统计公报 [Shenzhen Statistical Communiqué on National Economic and Social Development in 2010].” May 17. https://www.sz.gov.cn/zfgb/2011/gb743/content/post_4985524.html.

Shenzhen Municipal Archives. 2023. “深圳故事|特区发展的‘第一桶金’:‘三来一补’ [Shenzhen Story | The ‘First Pot of Gold’ for the Development of the Special Economic Zone: ‘Three Processings and One Subsidy’].” January 4. https://www.szdag.gov.cn/dawh/tqssn/content/post_930475.html.

Shu, Yunguo. 2012. “金融危机与非洲对外关系 [The Financial Crisis and African Foreign Relations].” West Asia and Africa, December 10.

Southcn.com. 2008. “汪洋回应‘不救落后生产力’[Wang Yang Responds to ‘Guangdong’s Decision of not Saving Its Backward Productivity’].” November 21. https://news.ifeng.com/mainland/200811/1121_17_888656.shtml.

State Council of the People’s Republic of China. 2015. “国务院关于印发《中国制造2025》的通知 Notice of the State Council on Issuing ‘Made in China 2025.’” May 19. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2015-05/19/content_9784.htm.

Wilson, Barry. 2019. “New Heart New Territory.” January 3. https://www.hkiud.org/en/articles/hkl/hkl_190103.php.

www.gov.cn. 2008a. “国务院常务会议部署扩大内需促进经济增长的措施 [The State Council Executive Meeting Deployed Measures to Expand Domestic Demand and Promote Economic Growth].” November 9. https://www.gov.cn/ldhd/2008-11/09/content_1143689.htm.

www.gov.cn. 2008b. “广东省召开推进产业转移和劳动力转移工作会议 [Guangdong Province Holds a Meeting to Promote Industrial and Labor Transfer].” May 30. https://www.gov.cn/gzdt/2008-05/30/content_999009.htm.

www.gov.cn. 2016. “从‘中国制造’到‘中国智造’,制造业之路国务院今年这样走 [From ‘Made in China’ to ‘Smart Manufacturing in China,’ the State Council’s Path to Manufacturing This Year].” December 26. https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-12/26/content_5152990.htm.

Xinhuanet. 2025a. “中共中央 国务院印发《乡村全面振兴规划(2024—2027年)》[The CPC Central Committee and the State Council Issued the ‘Rural Comprehensive Revitalization Plan (2024-2027)’].” Www.Gov.Cn, January 22. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/202501/content_7000493.htm.

Xinhuanet. 2025b. “激发高质量发展的更强大动力——中国推进供给侧结构性改革深度观察 [Stimulating a Stronger Impetus for High-Quality Development: An In-Depth Observation on China’s Supply-Side Structural Reform].” June 7. https://www.gov.cn/yaowen/liebiao/202506/content_7026829.htm.

Zheng, Liangyu. 1991. “深圳市国民经济和社会发展十年规划和第八个五年计划纲要 [Shenzhen’s Ten-Year National Economic and Social Development Plan and Outline of the Eighth Five-Year Plan].” October 30. https://www.sz.gov.cn/zfgb/1991/gb22/content/post_10030121.html.

Zhou, Guiqing. 2019. “东莞两年完成51263家散乱污企业综合整治 [Dongguan Completed the Comprehensive Rectification of 51,263 Scattered, Chaos, and Polluting Enterprises in Two Years].” China Forum of Environmental Journalist, October 16. https://www.cfej.net/pgt/201910/t20191016_737940.shtml.

Zixi Zhao is a PhD student in Cultural Anthropology at Duke University. He works on rural migrant workers and their navigation through urban transformation in Shenzhen, China.

To cite this essay, please use the bibliographic entry suggested below:

Zixi Zhao, "‘Replacing the Bad Birds’: China's Domestic Industrial Upgrade and its Implications for China-Africa Relations,” criticalasianstudies.org Commentary Board, January 22, 2026; https://doi.org/10.52698/TEOU1660.