Special Series: "New Directions in Africa-China Studies" | Fidele B. Ebia, When Chinese Manufacturers Become Traders

Since the early 2000s, Togolese traders have served as major distributors of Chinese-manufactured commodities in West Africa. This system of distribution enabled West African large traders, as well as wholesalers and petty sellers, to capture significant profit from global value chains. Today, however, Chinese traders affiliated with manufacturers back home have begun inserting themselves into the downstream end of value chains, thus cutting Togolese traders out of their distribution networks, with serious implications for local economies.

Based on interviews I conducted with and about newly-arrived Chinese traders in Togo in summer 2024 and January 2025, this essay examines the recent evolution of China-Togo value chains through a single case study, that of African Print Textiles (APT). It also briefly explores the policy and developmental implications of this intervention and asks why it is occurring now—and suggests that recent changes in Chinese state policy that prioritize IT over manufacturing, coupled with the effects of blockages in these value chains during COVID-19, are responsible.

* * *

African Print Textiles have a long, fabled, and complex history in West Africa.

APT is a multi-colored fabric that is widely consumed by West Africans. Initially produced in Europe in the early 1900s, it captured the imagination of coastal West Africans because of its bright, durable colors and its wax printing process, a process appropriated from batik during the Dutch colonization of Indonesia. Today, this cloth has become a mark of distinction and “African” identity, and is standard attire for West Africans, worn on everyday as well as special occasions (Ebia, 2023; Ebia & Horner, 2025).[1]

To facilitate the sale of “Dutch Wax” in West Africa during the 1930s, its European manufacturers collaborated with African traders whose local knowledge was integral to making APT accessible to West African markets. These traders also had significant input into the APT production process, traveling each year to Europe to advise Dutch manufacturers on color and pattern selection. These cloth traders, many from Togo, built a lucrative trade and became known as “Nana-Benz,” because of the automobiles they purchased with the wealth they acquired from the APT trade. Their wealth and reputation—they became local culture heroes—was not only personal but also national and regional. By the 1980s, their earnings were larger than those of the Togolese state, and it was said of Nana-Benz that it was they who kept the country afloat (Sylvanus, 2016).

In 1994, this enormously successful North-South value chain was threatened by the dramatic rise in cloth prices brought about by the French devaluation of the FCFA currency, which doubled the cost of imported APT. Devaluation came on top of SAP austerity measures imposed on African countries by the World Bank and IMF in the 1980s, privations which made APT too expensive for most West African consumers, and Nana-Benz lost much of their market.

In an unforeseen conjuncture of events, China, now emerging as “the factory of the world” (Sun, 2017), began manufacturing imitation APT at one-tenth the cost of Dutch cloth, and a new set of Togolese traders, referred to as “Nanettes” (“little Nanas”), began to distribute Chinese APT in Togolese and West African markets. Nanettes, like their Nana-Benz predecessors, played important roles in exchanging knowledge and information with Chinese manufacturers in order to perfect APT design, pattern and color.

In the early 2000’s, APT was considered low quality and barely acceptable to West African taste, but today imitation Chinese APT—even when “fake,” a copy of “real” Dutch—is widely traded on the West African market and is seen as near-Dutch quality. In an attempt to adapt to the competition from China, the Dutch manufacturer of the N-S chain, Group Vlisco, restructured its value chain, opened APT garment boutiques in West African capitals, and limited the role and income of Nana-Benz. No longer the grande dame traders of before, they are today little more than retailers. And Vlisco is a shadow of its former self, selling luxury/high-end APT to those elites who can afford it, cloth which today lies beyond the reach of everyday consumers (Ebia & Horner, 2025).

One of the distinctive features of APT value chains is that they have chain-like distribution networks which connect the large traders to local informal markets. APT cloth is sold in bolts or “pagnes,” not as finished garments; it arrives at the Lomé port in long sheafs in plastic bags—thus, as incomplete products—where they are cut (broken down) into pieces that are passed, often on credit, from seller to seller—the trader sells it to wholesalers, who sell it to vendors, who sell it to street sellers, who sell to consumers. These consumers then take the unfinished cloth to neighborhood tailors and seamstresses for fashioning into garments, according to consumer taste.

In this way, the APT distribution chain in Togo brings into employment an army of local vendors and petty traders—drawn from the mass of precarious informal workers who constitute over 80% of Togo’s workforce.

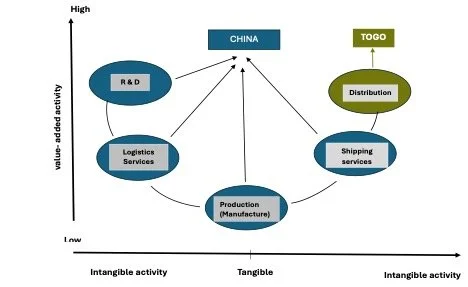

Figure 1: Mapping Africa-Togo APT value-chains. Source: Author

Figure 1 illustrates the many local actors involved in the China-Togo APT value-chain, and hints at the consequences of its transformation—when Togolese and other West Africans are no longer the only distributors or importers. This chain is composed of two main segments: a production segment located in China with its many factories, and a distribution/marketing segment in West Africa run by local traders. Many other informal actors are also linked to the Togolese distribution segment: wholesalers, vendors, street vendors, and tailors whose livelihoods depend on its distribution in West African markets and neighborhoods.

* * *

Global value chain theory enables us to parse the history and evolution of value chains and to measure where value capture occurs along the chain. It also permits analysts to evaluate where inequalities in value capture arise along the chain (Kaplinsky & Morris, 2000; Henderson & al., 2002; Bair, 2005; Gereffi & al., 2005; Gereffi, 2018).

Despite calls within the GVC literature to focus on South-South value chains (Horner, 2016; Horner & Nadvi, 2018), most value chain research remains focused on North-South chains and on these chains’ distinctive top-down lead firm governance. Yet, S-S chains are rapidly expanding and becoming globally dominant (UNCTAD, 2004; UNCTAD, 2024), and many exhibit a form of governance that is not lead firm-directed (Haugen, 2018; Tessmann, 2018).

My own work (Ebia, 2023) brings the study of traders into the discussion and argues that they replace lead firms in S-S (APT) value chains, governing the chain through a regime that is horizontal and diffuse rather than hierarchical. Moreover, traders’ ability to link formal and informal markets gives them advantage in a region of the world where up to 80% of the economy is informal.

Crucially, for the purposes of this paper, GVC theory demonstrates, as illustrated in Figure 2, that despite the insistence of economists and development economy theorists, production and manufacturing are not high value-adding activities—and are not necessarily sustainable ways of contributing to the economic development of a country.

Figure 2: China-Togo APT smile curve. Source: Author adapted from Fernandez-Stark & Gereffi (2016. P.14)

As the field of Business Studies’s well-known “Smile Curve” indicates, “intangibles” in the production of commodities—R&D and distribution, for instance—are higher value-added activities than production and manufacturing. This is relevant to the case of APT in Togo, which captures value from the “intangible” activity of distribution.[2] While, in the case of Chinese APT, China captures some value from manufacture, Togo captures greater value from distribution—which constitutes 70% of the value of a cloth segment (“pagne”) of APT when sold on the street (Ebia, 2023).

* * *

APT distribution is regulated by law in Togo, and should only be carried out by Togolese and West African traders. However, during COVID-19, this requirement was relaxed. Because the borders were closed and Nanettes were unable to travel to China, some began loaning their import licenses to Chinese traders to import APT to Lome on their behalf.

During interviews I conducted in December 2024, I learned that during COVID a well-known but aging Nanette in Lomé, Mme Ablagan, could no longer travel to China to ensure the quality of her cloth. When she was swindled by a Chinese factory—which sent her an entire container of low quality APT for which she’d paid quality prices—she decided to loan her trader’s license to a Chinese entrepreneur she knew, who offered to help her import APT. This worked well for Ablagan at the time but it also planted a seed with the Chinese man. Through this experience, he learned the tricks of the trade and saw an opening. With time, this man became not only an importer of APT but also a trader—a role only Nanettes had played until then.

Because Togolese border agents can be bribed—it is not difficult for Chinese traders to slip envelopes into their hands in order to get large cloth containers through the port—and because S-S trade is more open-ended, improvisational, and flexible than N-S trade (Gambino & Franceschini, 2025; Ebia & Barrientos, n.d.), this Chinese trader and others quickly discovered that they could take advantage of the informal and largely unregulated nature of the distribution system. To do so, they recruited young Togolese assistants to work with them—sending them to the Confucius Institute in Lomé for training and to learn Chinese, and promising them internships in China. Not only did these assistants teach their Chinese patrons the market in Lomé but also they helped them acquire licenses—in the names of the assistants—which enabled them to conduct trade in Togo. Their enterprises, however, remain in the shadows: unlike Togolese traders, whose boutiques are visible and well-known in the market, Chinese APT shops (“magasins”) are unmarked and hidden in high-rise buildings and warehouses. Today, there are up to ten Chinese import businesses representing Chinese trading companies in Togo.

From the standpoint of the national economy and Togo’s most valued commodity, this recent development within the APT value chain, risks sidelining Togo’s large cloth traders and threatens thousands of informal economy jobs. It also means the flight of capital from West Africa to China. Whereas Nana-Benz and Nanettes, with an enterprise “larger than the Togolese state,” reinvested their millions back into the Togolese economy (diversifying their businesses, purchasing real estate, building palatial residences in Lomé), Chinese traders typically repatriate the profits from their business back home.

For some, conducting retail on the African frontier is an attractive alternative—and still being connected to China enables these entrepreneurs to benefit from all the advantages of back home—financing, smart technology, digital services.

It is important to add here that recent changes in Chinese state policy have contributed as well. In China, the development plan is shifting from production and manufacturing to high tech investment (prioritizing IT over manufacturing, thus pushing Chinese entrepreneurs to search for new avenues of value capture) and making Africa an attractive alternative for young middle-class entrepreneurs (see Zhao, this collection). As well, according to a young Chinese entrepreneur I befriended in Lomé, Chinese low-income youth who are educated may no longer want to end up like their parents—working in factories—and are now attracted to careers outside China. Finally, during Covid-19, some Chinese middle-class private entrepreneurs experienced bankruptcy and discontent at home, and started exploring foreign markets.

* * *

In the China-Togo relationship, there has been a shift from end-of-the-20th century bilateral (state to state) relations and partnerships that focused on large infrastructure projects—stadiums, roads, bridges, hospitals, the “Palais des Congrès” that houses Togo’s legislature in northern Togo—all financed through loans/indebtedness via the large international banks, to smaller projects focused on privately-owned companies, individual entrepreneurs, Fintech and the digital. Today’s Chinese projects in Togo include investment in telecoms, insurance schemes and microlending, as well as private retail like the recently-built “China Mall” in Lomé, a Costco-style retail outlet that sells everything from home furnishings to groceries, at affordable prices (for the Togolese middle class)—and, of course, all manufactured in China. To this retail venture, I would add those Chinese traders inserting themselves into the APT value chain.

These shifts from infrastructure to the digital, and from state to private, are also tied to the advent of neoliberalism in Togo, namely to the 1990s privatization of state properties, the withdrawal of the Togolese state from the economy, and the opening of the economy to the market—at the insistence of the large international lending institutions (the World Bank and the IMF), who imposed privatization/marketization on Togo in return for debt adjustment (Harvey, 2005).

A key development and signature innovation of the neoliberal economy in Togo, also important to the history of APT, was the creation of a tax-free special economic zone at the Lomé port. This turn-of-the-century development facilitated and fast-tracked the flood of tariff-free Chinese imports into Togo that characterized those years and generated employment for large numbers of Togolese informal traders.

The late 1990s/early 2000s thus witnessed an almost seamless convergence of neoliberal marketization in Togo with the rise of manufacture in China.

At that time, it was win-win for these two global South countries, one “emerging,” the other “developing,” but both benefiting—as if turning the hierarchies of the world system upside down, the dream of the Bandung conference (Ebia, 2025). But with today’s restructuring and the shift from state to private power, China’s presence has become more hegemonic and detrimental to West African countries. Today’s private Chinese entrepreneurs, in pursuing their own interest and quest for profit—the ethos of neoliberal capitalism in which everything is dictated by profit maximization and the market—no longer abide by the spirit of Bandung.

*. * *

While not the main topic of this essay, I remain committed to seeking a solution to this conflict that would benefit both Chinese and Togolese and is consistent with the spirit of Bandung, in which S-S solidarity and cooperation was the order of the day (Ebia, 2025).

The import of manufactured goods from China constitutes one of the biggest sources of activity and revenue for West African city dwellers. Chinese products proliferate in Togolese markets, both formal and informal, and provide a livelihood for thousands of small and large traders. While the import and distribution of a commodity like APT will not displace smallholder sellers and street vendors in the short term (because Chinese are unlikely to be able to sell in markets where local knowledge prevails), it will affect the large traders—the Nanettes—who could well lose their lucrative trade. As already stated, their wealth is not only personal but also national.

Moreover, if Chinese take over the distribution segment of the value chain, it is likely that the profits made from Chinese investment in West Africa will be expatriated back home (Huang, 2024). By contrast, local traders, Nana-Benz and Nanettes, invariably invest their profits in Togo—where they are known for diversifying their holdings and creating jobs beyond the APT sector (Sylvanus, 2016).

In the case of APT, there is a blindness and failure of the Togolese state to imagine and design trade strategies that would protect both domestic entrepreneurs and foreign investors in order to stimulate a sustainable growth. Given the rapid and continuing expansion of South-South value chains and the complexities of the trader distribution regime, one policy intervention that could make a difference would be for countries like Togo who do not manufacture primary products but who participate in GVCs through trade and import to better police those foreigners engaging in distribution. If they do not, a country like Togo will become little more than a country of consumers, with little added to the national economy—for then they would neither produce nor distribute.

A second potential intervention: tax-collecting from foreign businesses should become a priority. If, in addition to supplying Togolese citizens with needed commodities, the aim of FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) is taxation and the job creation, it should be a priority to enforce the policy. If Chinese can entice young Togolese to give them permits to import APT, and Chinese are able to bribe state officials at the port to allow their goods to enter, it is likely they will do all they can to evade taxation. And, if taxes collected are not re-invested for the national interest—and not stolen by state officials—there will be many foreigners in these countries trading and getting rich while the locals continue to live in poverty—lacking minimum public services such as hospitals, electricity, clean water and schools, without forgetting the lack of jobs. Such a situation reproduces African “underdevelopment” (Rodney, 1972) all over again.

In the mid-term, it is crucial to avoid history repeating itself. Taking APT history, for instance, Nana-Benz formerly had a monopoly on the distribution of Dutch APT within West and Central Africa, but today they have become mere retailers with a trade contract with the Dutch company Vlisco that now controls the entire value chain from production to distribution. The same is about to be repeated between Chinese and Nanettes, who, let it not be forgotten, worked alongside Chinese manufacturers at sites of production—to enhance the designs, colors and quality of APT. Today, Chinese are imposing themselves on an APT market in Togo where the competition between them and Nanettes will always be uneven. Already, the APT sold by Chinese is at factory prices, an advantage that local Togolese traders do not have. One can imagine that, slowly but surely, Nanettes will abandon going to China, instead buying from Chinese in the Lomé market. Then, in the blink of an eye, Nanettes will become retailers rather than traders,[3] while Chinese themselves will monopolize both production and distribution functions of cloth consumed in West Africa. Perhaps, one day in the not-so-distant future, Chinese will also take charge of tailoring and/or have inexpensive APT garment shops with Chinese tailors at the edges of the market, taking jobs from thousands of local tailors and seamstresses.

My final recommendation for the long term is to suggest that we are at a propitious moment for Togo to reconnect to APT production with the help of Chinese private entrepreneurs. Sooner or later, sub-Saharan African countries must reconnect to industrial production (Sun, 2017),[4] and where better to start than with goods like APT which are largely consumed on the continent. China’s position is capital here, in the sense that Chinese individual entrepreneurs are going abroad to invest. Following a well-designed strategy, why not encourage them to assist in relocating APT factories from China to Togo (and other West African countries) rather than taking over APT distribution chains?

To restate one more time all the advantages of bringing production to West Africa: more jobs for locals, more taxes for the state, and, most importantly, the transfer of skills and knowledge of production to the African continent.

* * *

Let me conclude by saying that the take-over of APT by Chinese traders is only the tip of the iceberg; other value chains, among them aluminum and house tiles, both used in today’s booming housing market in Lomé and both sourced from China, are vulnerable to a similar take-over.

The consequences of this take-over of trader-directed West African value chains are perhaps more serious in the long term than anything that has come before; thousands of jobs, of large and small traders, are at stake—jobs that have long provided a livelihood for millions of distributors across the continent.

References

Bair, J. (2005). Global capitalism and commodity chains: looking back, going forward. Competition & Change, 9(2), 153-180. doi:10.1179/102452905X45382.

Deleuze, A. (2018). Itineraire de vie d'un textile: etude sur les usages locales du tissu-pagne à Lomè (TOGO). [Unpublished doctoral dissertation] University of Laval. hdl.handle.net/20.500.11794/32965.

Ebia, F. (2023). Traders in global value chains: the case of Togolese female traders and African print textiles. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation] University of Manchester. https://research.manchester.ac.uk/en/studentTheses/traders-in-global-value-chains-the-case-of-togolese-female-trader.

Ebia, F. (2025). China-Togo value chains: Nanettes and the trade of African print textiles. Bandung Conference-University of Lomé.

Ebia, F., & Barrientos, S. (n.d.). Traders and informality in global value chains: African print textiles in Togo. under review at Development and Change.

Ebia, F., & Horner, R. (2025). Colonial threads to made in China: Togo and the restructuring of African print textiles value chains. Geoforum, 163, 1-10. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2025.104297.

Edoh, A. (2016, September). Doing Dutch wax cloth: practice, politics, and 'the new Africa'. [Unpublished doctoral disssertation] MIT. doi:10.1093/jdh/epw011.

Gambino, E., & Franceschini, C. (2025). Flexible embeddedness: how Chinese lead firms internationalise in Africa. Review of International Political Economy, 1-31. doi:10.1080/09692290.2025.2538187.

Gereffi, G. (2018). Global value chains and development: redefining the contours of 21st century capitalism. Cambridge University Press.

Gereffi, G., & al. (2005). The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy, 12(1), 78-104. doi:10.1080/09692290500049805.

Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford University Press.

Haugen, H. (2018). Petty commodities, serious business: the governance of fashion jewellery chains between China and Ghana. Global Networks, 18(2), 307-325. doi:10.1111/glob.12164.

Henderson, J., & al. (2002). Global production networks and the analysis of economic development. Review of International Political Economy, 9(3), 436-464.

Horner, R. (2016). A new economic geography of trade and development? Governing South–South trade, value chains and production networks. Territory, Politics, Governance, 4(4), 400-420. doi:10.1080/21622671.2015.1073614.

Horner, R., & Nadvi, K. (2018). Global value chains and the rise of the global South: unpacking twenty-first century polycentric trade. Global Networks, 18(2), 207-237. doi:10.1111/glob.12180.

Huang, M. (2024). Reconfiguring racial capitalism: South Africa in the Chinese century. Duke University Press.

Kaplinsky, R., & Morris, M. (2000). A handbook for value chain research (Vol. 113). Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex.

Marguerat, Y. (1995). Dadja ou l'usine aux champs: industrialisation et émergence du fait urbain au Togo. Villes en Parallèle, 22(1), 130-157.

Prag, E. (2013). Mama Benz in trouble: networks, the state, and fashion wars in the Beninese textile market. African Studies Review, 53(3), 101-121. doi:10.1017/asr.2013.81.

Rodney, W. (1972). How Europe underdeveloped Africa. Black Classic Press.

Rodrik, D. (2016). Premature deindustrialization. Journal of Economic Growth, 21(1), 1-33.

Sylvanus, N. (2016). Patterns in circulation: cloth, gender, and materiality in West Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tessmann, J. (2018). Governance and upgrading in South-South value chains: Evidence from the cashew industries in India and Ivory Coast. Global Networks, 18(2), 264-284. doi:10.1177/1024529419877491.

UNCTAD. (2004). The new geography of international economic relations. Background Paper No. 1. unctad.org/system/files/official-document/tdb51d6_en.pdf.

UNCTAD. (2024). Rethinking development in the age of discontent. UNCTAD. https://www.developmentaid.org/api/frontend/cms/file/2024/10/tdr2024_en.pdf.

Notes

[1] This paper relies on data collected during PhD research in the APT markets of Lomé. I interviewed over 100 cloth traders, port agents, textile company employees, and state officials over 20 months in 2019-2021, and returned for follow-up research in 2024 and 2025. My thanks to Elisa Gambino who took me on as a research collaborator for a project about new Chinese entrepreneurs in Ghana and Togo supported by the University of Manchester.

There is a robust and nuanced literature within anthropology on the APT cloth trade in Lomé (Edoh, 2016; Sylvanus, 2016; Deleuze, 2018) from which I have drawn insight about the culture and fashion of APT in Togo. Sociologists and economists (Prag, 2013) have also offered important studies of APT beyond Togo’s borders.

[2] As do corporate giants Walmart and Amazon in the US context. Both are distributors or renters rather than manufacturers.

[3] A “retailer” is a contract worker, buying and selling cloth at market prices—a link in a lead firm’s value chain. A “trader” runs her own enterprise and directs (“governs”, in the language of GVC theory) much of the value chain—hiring local assistants and transporters, arranging cross-border logistics, contracting with petty distributors, negotiating and setting her own prices. All of a trader’s profits, which often run into the millions of dollars annually, are hers.

[4] During early independence in the 1960s, several West African countries—Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire, Nigeria and Togo—built their own APT factories. At this time, Togo’s state-owned Datcha factory began manufacturing an APT called TOGOTEX that was beautiful and widely-appreciated. Unfortunately, for a range of reasons (inadequate infrastructure, lack of manufacturing expertise—in what economist Dani Rodrik (2016) has referred to as Africa’s “premature industrialization”—this experiment failed and by the 1980s and 1990s most of these factories had closed (Marguerat, 1995).

Fidèle Ebia received her PhD in Global Development Studies from the University of Manchester (UK) in 2023 with a dissertation on value chains and African Print Textiles in West Africa. Her current research examines digitality and social media in Togo. She is currently a postdoctoral research fellow with the Africa Initiative at Duke University.

To cite this essay, please use the bibliographic entry suggested below:

Fidele B. Ebia, “When Chinese Manufacturers Become Traders,” criticalasianstudies.org Commentary Board, January 22, 2026; https://doi.org/10.52698/NBZA5213.